Because we feel unsafe, we plan our night with the idea that we’ll have to leave earlier because we need to use longer routes and think about what’s the best one for us to feel safe.

In the past few decades, this question of women’s safety in urban spaces has become a global societal issue and many researchers in gender studies and feminist geography have developed theories to highlight the roots of the problem and suggest solutions. Nevertheless, social/power relationship in society take time, sometimes generations to change so approaching this issue from an urban/transport point of view is quite interesting because making changes to the built environment or to a transport network can be done in a relatively short time.

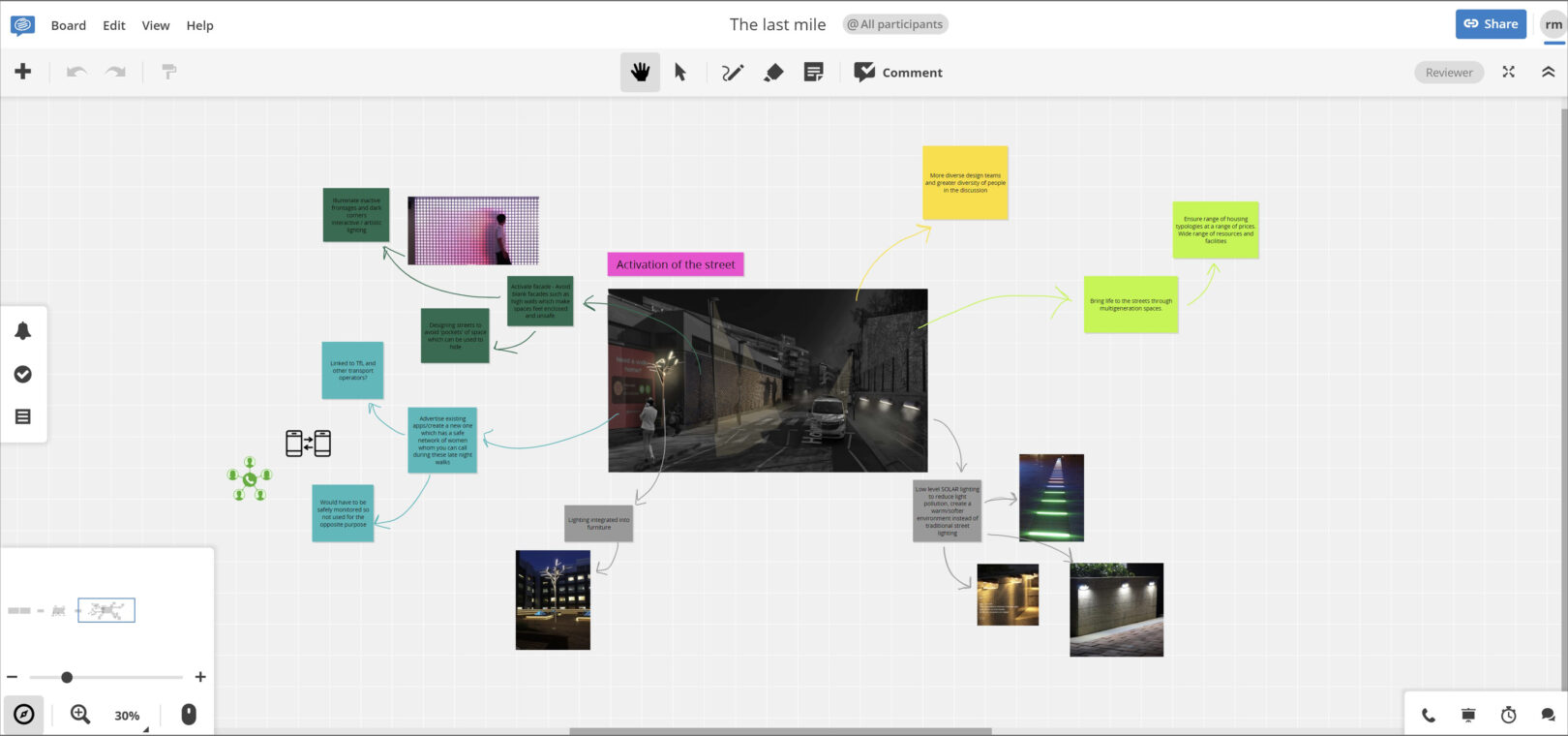

As designers, we felt it was intrinsic and crucial to understand how we can have an impact on this and we organised a Future Thinking session to talk about it, raise awareness among our peers and explore potential solutions that we – as designers – could implement to mitigate fear and improve the experience of women using public transport and navigating through public spaces.

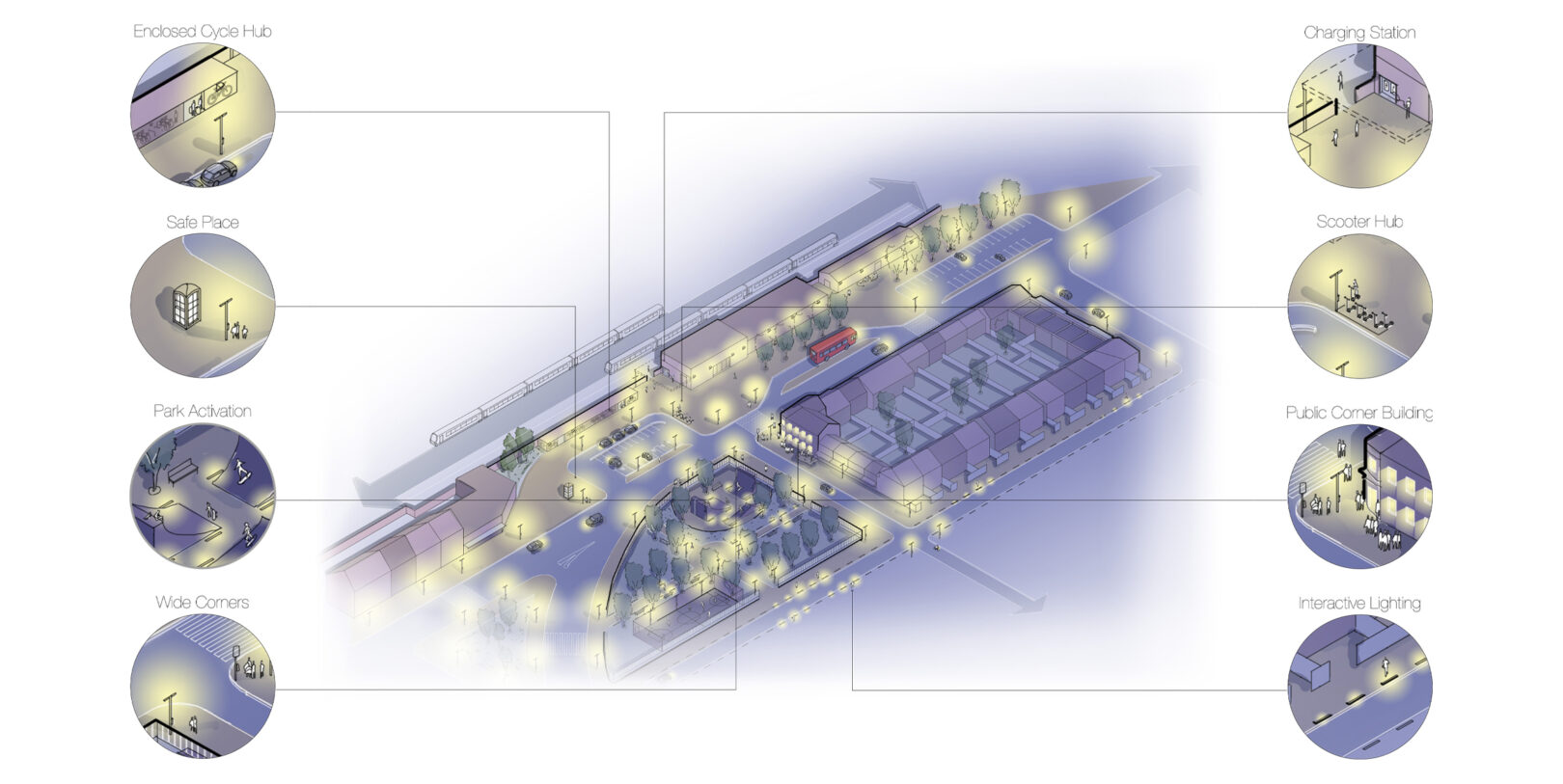

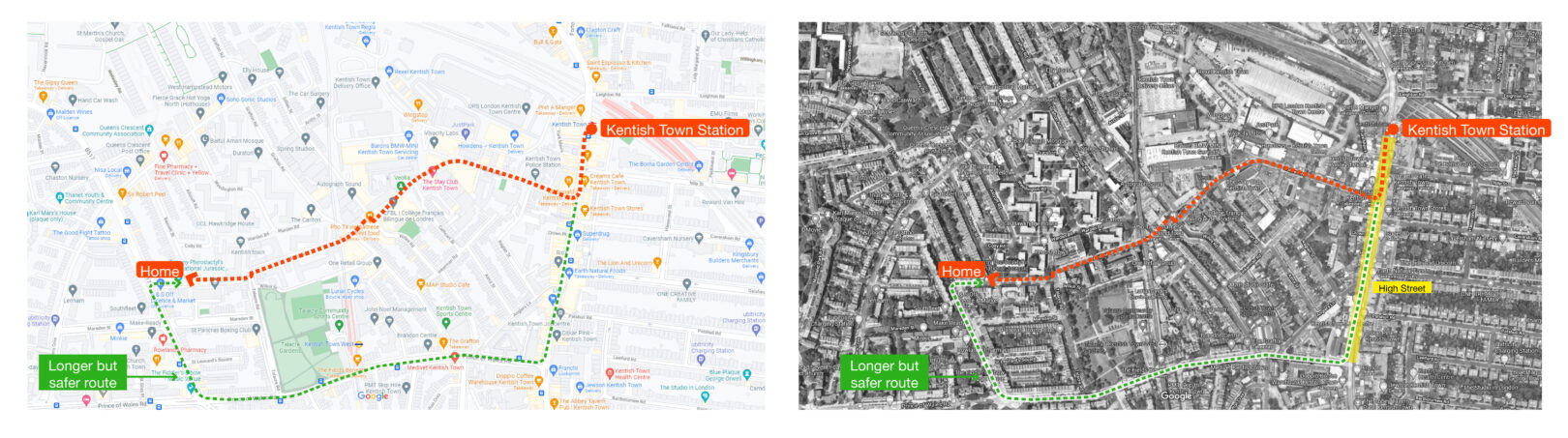

For these sessions, taking place across a week to involve as many people as possible, we asked everyone to think about gender inclusivity in transport and the public realm, by focusing on the ‘last mile’. The ‘last mile’ is the last part of the commute between a public transport station, whether it is a bus stop, a train station or something else, and the home. Our idea was to think about ways to improve this portion of the journey that is often forgotten, but that means so much to people, especially in terms of safety and security. Each group was assigned an area and a route from a public transport station to a home that was judged unsafe by a woman in the studio (see above).

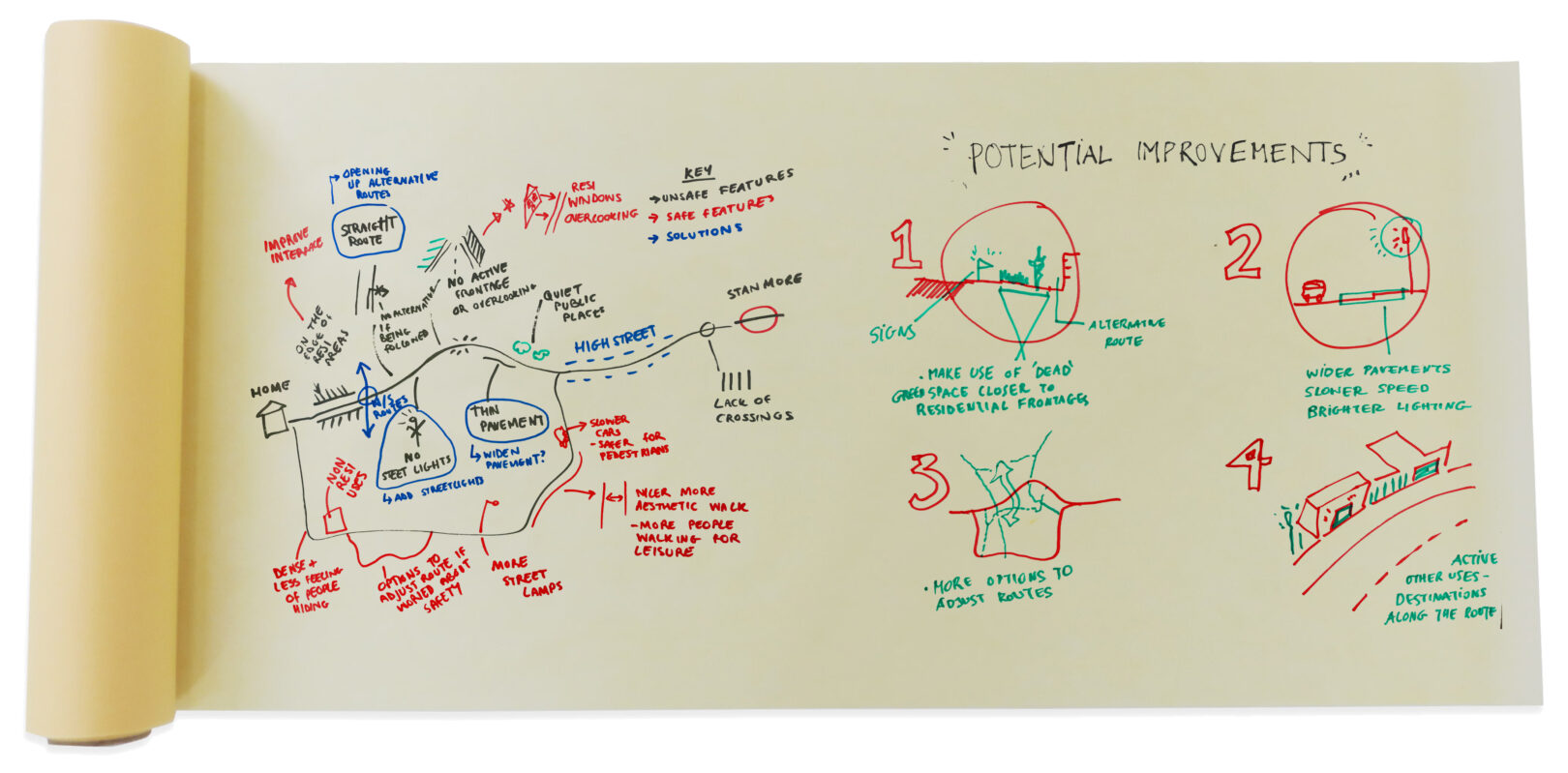

Each team, first focused on understanding why this route might feel unsafe: what are the elements of the streetscape contributing to this, are related to design characteristics or planning elements. And then, they were asked to suggest improvements or solutions to make these routes feel safer. Various themes emerged and although different sites were assigned to the different groups, similar issues and problems were highlighted, and common design solutions and ideas were presented. We organised the outcomes in two groups, Preventive Design Ideas (passive measures) and Emergency Ideas (reactive measures), with the aim to use these outcomes to raise awareness with our clients on future projects.

Preventive Design Ideas (passive measures)

These relate to all the design or planning measures suggested that would tend to make women feel safer while walking this last mile. The main idea was to work on the ‘urban senscape’ to improve the sensory experience of women. This could be done by enhancing visual and auditory environments for example: Having streetlight integrated within public realm structures, activating facades with artistic or interactive lighting, developing a dynamic lighting system that would illuminate a route as you walk through it or exploring the potential of Sound Design which could give a sense that you are not alone in a space or generally make a space less quiet and deserted. Another idea related to the senses was to add colours and a greater diversity of materials such as mirrors within urban environments as this is often associated with safe and playful spaces.

Many groups mentioned the need to avoid blind spots and gaps between buildings and to design streets and public spaces with pedestrians in mind rather than car users.

Chamfered corners like in Barcelona for example, increased pavement width and more planting were among the various design ideas suggested to mitigate fear.

The other aspect discussed within the groups was related to planning ideas and decisions. We all know that deserted spaces or mono-functional areas generally lead to safety issues at night. To address this, we talked about the 10-15min walk city where every residential area would be within close proximity of a high-street or a local centre with a wider diversity of uses. It is all about activating spaces, whether it is a residential street with a pub on the corner, a park with a skate park or basketball area or a public space with places to eat or drink (day-time and night-time activity). Generally having ‘eyes on the streets’ and multi-generational & multi-purpose spaces are important elements when it comes to design and planning. The distribution of land use is key and this is something that designers,masterplanners and planners should always have in mind when working on new areas or regeneration projects.

Emergency ideas (reactive measures)

The second theme that emerged from these discussions were reactive/emergency measures to assist/support women in situations where they feel unsafe or threatened. A lot of these ideas were based on digital support: street wifi and battery charging points at stations to ensure that women are always able to call someone in case of danger for example. Apps suggesting safer routes or digital networks of women who can call each other while walking alone late at night in different parts of a country could be implemented rather easily as innovative solutions to support women.

Another emergency design idea mentioned was to reinstate telephone boxes as street furniture that could be used to call emergency services and potentially lock yourself inside in case of danger. Panic buttons placed on street furniture could also dissuade offenders from attacking if they know that victims can easily set off an alarm or reach the police/emergency services. And the availability of bikes or e-scooters at stations that can be used as an alternative to walk the last mile can also represent innovative solutions at a neighbourhood scale to ensure that women are safe on their journey back home.

Conclusion

Overall, everyone who took part in these sessions agreed that women should be more involved in design and planning so they can have a voice and these ideas can be implemented to improve the experience of women. Ultimately, that could help restore gender equality and even go beyond that:

Throughout history, public spaces have mostly been a male-dominated sphere characterised by social and political activity and even today, the cities we live in are mostly designed by men, for men, and are often unsuited to groups such as children, the elderly, the disabled, women or migrants, for which access is sometimes restricted for physical or psychological reasons. All the ideas mentioned above would benefit not only women but all these minority groups and could help create more inclusive and diverse urban spaces and healthy cities.

References

[1] Femicide Census report released 13th February 2022

[2] On the street or walking around (42%); in a club, pub or bar (31%); on public transportation (28%)

[3] 2021 UN Women UK YouGov - Prevalence and reporting of sexual harassment in UK public spaces MARCH 2021